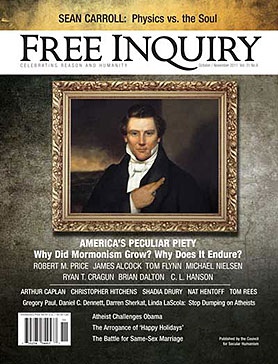

The following is an article I wrote for the October / November 2011 issue of Free Inquiry (the magazine of the Council for Secular Humanism), reposted here with permission from the editors. The Oct/Nov issue is a special issue on Mormonism, and one other MSP regular also contributed to it.

The following is an article I wrote for the October / November 2011 issue of Free Inquiry (the magazine of the Council for Secular Humanism), reposted here with permission from the editors. The Oct/Nov issue is a special issue on Mormonism, and one other MSP regular also contributed to it.

I am an atheist, but I grew up Mormon. My children have asked their grandparents and others about religious belief, about how it works, to try to understand it. But for all of their interest and curiosity, I doubt they’ll truly understand what it’s like to be a part of a religious community, and to truly believe in it. I wouldn’t recommend raising children in religion just so they’ll have the experience, but as for myself, I wouldn’t trade in my experiences for a non-religious background even if I could.

One of the biggest lessons I’ve learned is that a single claim can seem either obviously crazy or perfectly reasonable depending on how you’re exposed to it. Consider the Mormon belief that God was once a human and that humans can become Gods. As a teenager, it was an epiphany for me to encounter Christians who scorned and ridiculed this belief — not for being a deadly heresy, but for being obviously absurd. Meanwhile these same Christians believed in an omnipotent three-in-one God with no beginning who loves His human children, and promises them an eternity of unchanging subservience (best case scenario) or an eternity of torture. I’d been exposed (as least tangentially) to mainstream Christian beliefs my whole life, so their theology didn’t really shock me. But I was shocked by their crazy belief that Mormon theology was somehow objectively more crazy than their own theology.

This is a lesson that I’ve carried with me. For example, one time some colleagues invited me to a Hindu Diwali celebration, and I was surprised to see people pouring milk and honey and orange juice over statues of their gods, apparently to please them. “Wow, that’s crazy!” I thought, and then I stopped myself. Crazier than symbolically eating your God? Or than putting olive oil on someone’s head to perform a faith healing?

So much of what seems normal and reasonable depends on the beliefs you’re brought up with and on the things the people around you believe. Other trappings can influence your perception as well, such as homeopathic medicines that are packaged up like real medicine and sold in an ordinary pharmacy. One thing I’ve learned is that the natural “That’s crazy!” reaction doesn’t always lead to a rational exchange of ideas. If a person thinks that claim X is reasonable, and you say it’s obviously crazy, then in that person’s eyes you may be the one who looks like a raving lunatic. A lot of times you need to start by understanding why belief X seems reasonable to the other person before you begin to discuss it.

Spending my formative years in a minority religion has shaped my perspective and has helped shape who I am. Note that I wasn’t raised in some sort of isolated community of believers who fear and shun all contact with the outside. I went to an ordinary suburban High School that had only a handful of Mormon students, so most of my friends were not Mormon. On the other hand, Mormonism is a time-consuming religion that requires a lot of socializing with other believers, so it was as though I had one foot in one community and one foot in another. Thus I observed how minorities are judged (and misjudged). And I learned that being different is more than OK — it’s something to be proud of.

Now that I’m an atheist, I have additional perspective. I haven’t forgotten my past, so it’s a little like being bilingual. I can translate between two communities. On the Internet, I can correct errors and mis-impressions on one side or the other. On the Mormon side, you naturally see people who believe in the usual stereotypes about atheists: that they’re miserable, amoral nihilists, or whatever. Sometimes on the Bloggernacle (the network of faithful Mormon blogs) people write posts using those stereotypes as basic “everybody knows”-type background assumptions about atheists. I’m one of the ex-Mormon atheists that help to challenge the stereotypes not only by posting comments directly on posts that misrepresent atheists, but also by maintaining a long-term personal blog about my ordinary life as a mild-mannered mom.

On the other side, I can correct erroneous claims people make about Mormons and Mormon doctrine. In particular, there’s a lot of confusion about polygamy — mostly due to the publicity wing of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints broadcasting misleading half-truths like “We have not had any connection with polygamy for over a hundred years; we have no connection with any modern polygamist groups; the modern polygamist groups are not Mormon; end of story, stop asking us about it.” In reality, the modern Mormon polygamist groups are branches of the same tradition, they have as much right as any other branch of Mormonism to self-identify as “Mormon”, and while the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the branch with the pairs of missionaries with suits and bikes and little name-tags) renounced the modern practice of polygamy, it hasn’t renounced it as an eternal doctrine — notably their “eternal families” include polygamous families.

My Mormon past puts me in a unique position to provide constructive criticism to the Mormon community. When I encounter Mormons talking amongst themselves, I know the lingo, and what’s more, I grok what they’re talking about because I’ve lived it. We have shared experiences. When the Mormons were working to get Proposition 8 passed in California, I could talk to them about what’s wrong with that, without having them immediately dismiss me as someone who hates/misunderstands Mormons. I can approach them — not as someone who thinks Mormons are crazy cultists — but as a family member who just wants to see my own people do the right thing. I currently write for the group blog Main Street Plaza, and we discuss politics with the faithful all the time. The leaders and the publicity arm of the CoJCoL-dS constantly spread memes like “Gay marriage is a threat to our freedom of religion,” and “people who criticize the Mormon involvement in Proposition 8 are hypocrites because they’re bigoted against Mormons,” etc. As a member of the family, I can discuss with faithful Mormons what’s wrong with those messages in a calm and constructive manner.

As an aside, I want to make it clear that — while I’m interested in engaging thoughtful believers in constructive, civil dialog — I’m not denouncing other approaches. No matter how nice and well-meaning I may be, “apostates” are viewed with suspicion in Mormonism and in many other religions. That’s why I don’t want to disparage the outspoken “new atheists” who are highly critical of religion. They’re the ones who open up the middle ground where “nice” tactful atheism can occur — by moving the poles of the debate. You’re misunderstanding the dynamics of the debate if you think that angry atheists harm the position of the bridge-building atheists. Really it’s the opposite. The only reason religious people see you as a nice atheist — as opposed to seeing you as a servant of Satan who should have no place in the discussion — is because there’s someone else out there who’s less “nice”, providing contrast. If any atheists are advocating crime or violence or taking away religious people’s civil rights, then I’ll denounce them for it. But if they’re offending people by challenging the wrong-headed notion that religion has a monopoly on morals and ethics, I’ll thank them for putting those points on the table of discussion.

Actually, the alliance between the Mormons and the rest of the Religious Right is one of my favorite topics to discuss with believing Mormons. Naturally, I think that Mormons — being a minority religion, like the Jews — need to understand the importance of protecting the rights of minorities. The problem is not merely the fact that the Evangelical Christians think that Mormonism is a dangerous cult. It’s possible to make political alliances with people that you don’t like personally. But as I (and even many faithful Mormons have pointed out), it’s not in the Mormons’ interest to promote laws allowing majority religions to impose their beliefs on minorities — such as encouraging a precedent where a 51% majority can enshrine religious-based discrimination in the California constitution. When Mitt Romney gave his famous speech describing American political discourse as a “tapestry of faith,” many of the Mormon blogs fawned all over this one-ended bridge towards the Christian Right’s private club. And I was right there on Main Street Plaza to present the view that the speech was more about exclusion than inclusion, and to direct people to articulate articles explaining the following: “In a speech Romney was forced to give because he feared unfair discrimination, Romney did not stand against intolerance. Instead, he simply asked that it not be directed against him, a man of faith. You can be intolerant, but do it to them, over there. Theyre even more different,” and “Romney opposes bigotry in self-defense, not in defense of others, which is to say that he does not really oppose it at all.”

Another central part of my online work is to help build a community for former Mormon bloggers and encourage harmony and understanding within mixed-belief families. For years I’ve been gathering up former-Mormon bloggers into a huge blogroll called Outer Blogness, and I do a weekly link roundup (Sunday in Outer Blogness) to encourage people to visit each other’s blogs. Faithful Mormons naturally have a community of people to share their faith experiences with (at church), but losing belief can be incredibly isolating because in real life there’s very little context for sharing your experience with others. Family members and people at church typically find a loss of faith very threatening, and often react with fear and hostility rather than understanding. As soon as people get online, they’re usually pleasantly surprised to discover a whole world of others who have gone through similar experiences. And they can share strategies, including ideas on making the transition smoothly and on maintaining loving ties with family members who still believe. That was also the theme of my novel ExMormon: the grand comedy of growing up Mormon, caring about your Mormon community and identity, but then losing belief and reconstructing your expectations and your relationships. Believers have found the novel to be a fun and non-threatening starting point for understanding their non-believer friends and family members better.

Atheists who were raised in other religions can form the same sorts of bridges with their own communities. I encourage them to do so. It makes sense that — within the atheist community — secular Jews should take the lead when discussing Israel, and people raised Muslim should take the lead in discussions about problems in Muslim countries, for example. They have added perspective on the subject, plus they can be trusted not to be biased by racism against their group nor by believing that their group is doing God’s will. Being raised in religion isn’t better or worse than being raised without it. But I believe that those of us who were raised in religious communities have a special role to play, and we should step up and play it.

Some cultural theorists I’ve read have advocated writing about other people’s beliefs as if they actually were real, as opposed to writing about them as if real for that person or group. An example I’ve encountered in my workplace is that if you treat a schizophrenic’s hallucinations as if they were only real for that person, then you actually end up creating more distance in the long run. If you say, “Well, you might see that, and I can understand how that’s real for you, but please respect that I don’t see that,” the response tends to be, “So you think I’m crazy?”

I think the same thing happens with people’s beliefs — the only difference is that if you present yourself as an unbeliever to someone, you don’t necessarily create a feeling of loneliness, or instill that you think they’re “crazy,” per se, since they usually have a community to fall back on of people who don’t think they’re crazy. Now if a theist is currently reading this and is offended that I’ve compared theism to schizophrenia, then I would ask why they hold prejudice towards schizophrenics. We should remember that in many cultures, people with what we consider “mental disorders” were seen as prophets, seers and relevators, on top of the fact of there being gods, sprites and demons in the world.

The other reason it’s good to treat others’ beliefs as if they’re real is simply because of the way “objectivity” works. If in writing about Mormons, a situation comes up where Heavenly Father communicates this or that, then it’s unnecessary to say “And Sally believed that Heavenly Father communicated this or that.” If the reader is a nonbeliever, then the distance will already be there in the reading anyway; adding “Sally believed” merely tries to create a sense of pseudo-objectivity that ends up being read by a theist as atheistic subjectivity (or subjectivity based on a different set of beliefs). If there ends up being a question about the author’s belief or non-belief, then one can always research the author.

On the other hand, for as much fear as Christian communities attempt to instill that the world is being taken over by godlessness, it’s strange how polls demonstrate how Americans are twice less likely to vote for a presidential candidate who is an atheist than practically any other quality (Muslim, gay, adulterous, Mormon). So, I can see why atheists would like to create safe space for themselves as atheists, as opposed to just floating in general secular humanism that often overlaps with theism.

This is a very good point. If you want to understand the other person’s perspective, it’s useful to ask yourself “What if it were real? What would that be like?” and take that question seriously.

I think this depends on the context.

Even believers themselves recognize that they don’t always agree on what Heavenly Father says. I remember having lessons in seminary that if some guy at BYU tells you that he had a revelation that you should marry him, you shouldn’t simply assume it was really a communication from HF — even if the guy absolutely believes that’s what it was.

To avoid the loaded “judging others’ beliefs (as crazy or not)” question, I’d say there’s a difference between writing “Sally saw Tina at the reunion” and “Sally said she saw Tina at the reunion.” If I’m writing a story from Sally’s perspective, I’d use the former, but if someone is asking me whether Tina was at the reunion (but I wasn’t there myself), I’d probably go with the latter.

FABULOUS piece, Chanson. I read it all with interesting, but this was especially provocative:

I hope the magazine is getting good feedback about the piece.

Oops–read it all with interest.

Thanks!!

The point you quoted @3 is in response to a raging (and, IMHO, rather ridiculous) debate in the atheist community over what “tone” we should use. As if we should all use the same tone…!

I hope the magazine is getting good feedback too! I’ve already gotten positive feedback from the article via email, which is how I knew it had finally hit the shelves. 🙂

Yeah, but you yourself know what it’s like to be a moderator sometimes. It’s not hard to imagine a multi-pronged conversation where a bunch of angry atheists are lambasting a handful of theists, and the “nice” atheist can’t get a word in without negotiating tone. I guess one way to look at it is that the nice atheist is simply doing what she would normally do anyway, rather than something extra (AKA negotiating tone for the whole group), but I don’t think conversations about what the overall tone of a conversation should be necessarily means everyone needs to have the same tone.

Naturally.

I’m saying that there isn’t one canonical tone that works for everyone and all occasions — not that every tone is great for every circumstance. For example, as you point out, we’ve negotiated a particular tone here at MSP — but just because I like the way we do things here at MSP, that doesn’t mean other sites are wrong for having a different style and different goals.

I don’t participate in atheist blogs at all. Is there a lot of anger out there towards theists or is it just a few agitators that stir people up?

Interestingly — though Main Street Plaza is more an LDS-interest blog than an atheist blog — some people consider it to be an atheist blog because most of the regular contributors are atheists. Though you’re not technically participating in an atheist blog right now, you’re perhaps closer to it than you may realize.

It would be an interesting sociological question to study how much anger/agitation occurs on the Internet between various groups. The question “Is there a lot of anger?” requires a bit of perspective on compared to what? Compared to how much atheists love to write about science? Compared to how much anger Republicans express towards Obama? How much is “a lot”?

p.s. For a less facetious response to your question, perhaps start with Greta Christina’s classic piece on atheists and anger.

@chanson – Any participation by myself on this website should in no way be construed as an endorsement of its contributors’ wicked, naked godlessness… 😉

Based on the reading of that article with the associated comments, it appears that anger within atheism appears to run pretty deep. And I would say it is comparable to the anger found on a Recovery from Mormonism-type website. Unfortunately, I don’t think I could label this kind of attitude as “anger” per se. It appears to be contempt. And being a rather contemptuous and snarky person myself, I’m not saying this as a condemnation or self-righteously demanding that it be apolgized away, but more as a (limited) observation.

It IS an interesting sociological question. Can anger be a motivator to understand the other side? It’s interesting that there can be some much anger and hate between two groups, even if the differences may be more superficial than imagined. A lot of the things that Ms. Christina was angry about could easily cause anger in a staunch Christian. Rather than painting it as a theist/atheist divide, it could be that injustice angers humans. And there is a lot of injustice that relgion has nothing to do with. Why would religious injustice merit special attention? Because it is is more easily avoidable if only people would rely on a narrow set of mental processes that necessarily conclude in atheism and ignore any kind of transcendant experience that seems equally powerful, if not more so? And I respectfully submit that a deep-seated antipathy to religion says more about the holder of the anger than about religion itself. I don’t intend this as a critique of atheism or to say that their anger is misplaced. But i do think that there are hard questions that atheists should confront, given their stated preference for deep contemplation and reflection. And I also think that any person should be wary of anger transforming into contempt.

@11

Anger –> contempt –> bitterness. They’re a natural progression when injustice is ongoing and not resolved. There’s a temptation to blame the bitter person for breaking themselves, as if they failed to smile in the face of adversity, or failed to remove themselves from a damaging situation and create a new one. But I think it’s better to look at how the world broke them and/or in what ways they could not leave. For example, when people choose to leave the Church, they can’t just discard everything from their head. There’s a need for catharsis. Sure, sometimes people lash out at things and people undeserving, but oftentimes people sit and think on why exactly they’re not smiling anymore.

In my experience, barely anyone is all-around-contemptuous, where they’re angry to the point that they’ve locked themselves in an attic and spend their days staring down passersby through a dirty window. With the amount of injustice in the world, there’s about as much contempt as one would expect.

The theist/atheist divide is not always the most troubling, even for atheists. For example, I have a church right up the street that has a big rainbow sign that says “All Are Welcome” (gay-friendly), so when it comes to “homophobia,” at this particular church, theistic injustice is not an issue. But if you step back and look at the state of the country, you’ll find that only theistic groups are fighting marriage equality, so it’s worth examining what theism has to do with the matter.

“And I respectfully submit that a deep-seated antipathy to religion says more about the holder of the anger than about religion itself.”

Concern troll is concerned.

dpc — your comments are quite timely because it’s exactly the type of misunderstanding I was talking about strategies for avoiding (only from the other side).

The question of atheists (or exmormons) and anger essentially has a two-part response:

1. Sometimes there are legitimate reasons to be angry, hence anger should not be treated as a pathological response. (That’s the part explained in Greta Christina’s article I linked @10).

2. It is very hard for humans to empathize with groups they’ve mentally categorized as “other”. That’s just human nature. You accuse atheists of anger, bitterness, contempt, deep-seated antipathy, etc. I see these things aplenty in other groups as well, and I don’t see evidence that the negative traits are stronger (or significantly different) among atheists as among any other human group. And I see loads of love, joy, hope, wonder, curiosity, etc., among the people in the atheists community (like the folks you’ve met here). Remember: atheists are people too!

Any time you ask yourself “Why are those people like that?” you’re bound to come up with a over-simplistic (and probably wrong) answer based on stereotypes and prejudice, and based on seeing only a little part of the picture of what “the other” group is like. This is true whether your “other” group is atheists, Mormons, gay people, women, Chinese people, etc.

This is the point I discussed in my post on racism. You read Greta’s — read this one too.

If you really want to know why “those people are like that”, the first question you should ask yourself is “why are people like that?” In general. Including people from your own group. That will give you insights that will point you in the right direction.

First comment here at Main Street Plaza. I comment now because I too identify as Mormon/Atheist. I have never understood how people could leave this religion and attend another. I left Mormonism (belief, still have membership) through a dual paradigm shift. Shift #1 was because of reasonable and objective look at the history and evidence for our truth claims. Shift #2 came as I understood what the real evidence seems to purport, and that evidence seems to indicate that indeed we are an evolved primate, and that the naturalistic view of the cosmos seems to be more in harmony with our reality. I’m open to the idea of a God, but the sundry and various definitions, past and present do not, nor seem to be able to grasp its identity. If I find myself in front of this identity, I’m sure he’ll/she’ll appreciate the clean slate.

In the mean time, I find it difficult to understand why people would choose another church when deciding to leave this one. I agree that all of religion is in its own way completely unjustifiable if you use the same critical thinking that caused you to leave Mormonism.

I hate to admit it, but I seem to fall into the camp of “New Atheist”, and probably come across as strident or the like, but with the saturation that is religion in America, I can’t help but feel that any outspoken message critiquing any religion will sound shrill. Besides, if it’s not my content, but my delivery that sets me into the “angry atheist” camp by insisting we examine what and why we believe, then I’ll happily fill the role of tossing off as quickly as I can the wet blanket that is religion.

I hope my voice is welcome here.

Hi Rude Dog. I’ve seen your comments around (probably on fMh), and I’m glad to see you’ve found your way here.

I thought that too before the Internet came along. Or, more precisely, I thought “There are people like my dad — who were raised in a different religion, and convert to Mormonism in adulthood, but ultimately decide to go back to their earlier religion — and then there are people like me and my brothers, who use critical thinking on the claims of the religion, and end up as atheists.”

Since I’ve been on the Mormon and Ex-Mormon Internet, I’ve found that, in fact, there are a whole lot of different reasons for leaving Mormonism, and not all of them can be accurately described as primarily critical thinking.

That’s essentially the point I was making in the section that Holly quoted @3. How people perceive your message depends a lot less on how “strident” it is in absolute terms — it depends rather on where your message stands relative to the rest of the discussion. I always put the term “New Atheist” in quotes (as you have done) because it’s a label that has been imposed from the outside. As many people have pointed out, the only thing that’s really new about the “New Atheism” is that now atheists are a large enough segment of the population to show up on the mainstream radar.

But, when it comes to “angry” vs. “non-angry,” I’m not convinced that that’s a useful way to try to divide the “New Atheists” from anyone else. As I said above, most people occasionally are angry, often justifiably, and even the people who come off as angriest aren’t always angry.

The situation with ex-Mormons getting stereotyped as “angry” and “bitter” is very similar to the dynamic in the atheist community — see here and here (alternatively here and here) for discussion.

Thank you Chanson.

Is fMh down? Seems to be. Bummer. It’s been fun following the arc of that community’s development.