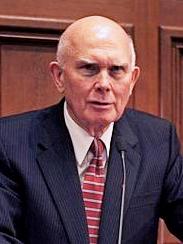

“It’s a study of power.” That’s how Taylor Petrey sums up his fascinating book on sexuality and gender in modern Mormonism, and that’s the phrase that kept going through my head as I listened to six hours of Mormon Stories podcasts about Dallin H. Oaks’s November 12 talk at the University of Virginia Law School. In comments described as “conciliatory” and “remarkably more open toward LGBTQ issues,” Oaks said that efforts to protect people from discrimination should be respected and balanced alongside religious liberty. He also denied established fact: that electric shock aversion therapy happened at BYU when he was university president.

I was left thinking that the talk was not about achieving reconciliation but maintaining power. There was a kind of gaslighting in not recognizing the power it has and the harms it has inflicted.

Coincidentally, @talkMormonism released its interview with Petrey the same day Oaks gave his talk. Petrey had started his research expecting to write about polygamy, but found that the issue of inter-racial marriage was much more fundamental to understanding modern Mormonism. ‘All arguments we are having about same-sex marriage today are literally repeats that we have about inter-racial marriage decades ago,’ he said. Arguments around changing women’s roles fall into the same pattern. [NB: I’m using single quotes to indicate something more than a paraphrase but less than a properly checked quote]

Prohibitions and restrictions are first justified as existentially essential to prevent the fall of civilization. As the Church adapts to society’s norms, justifications de-escalate as important for religious liberty. All the while, the Church diminishes and denies changes in its stances and policies. (Another kind of gaslighting.)

So the phrase ‘religious freedom’ rang alarm bells during Mormon Stories excellent and extensive analyses of Oaks’s public speech and the leaked Q&A with University of Virginia law students. One episode focused on Oaks’s legal strategies on LGBTQ issues; the other on the legacies of electroshock therapy and related harms.

Double language

Petrey (who has not, to my knowledge, commented on the UVA speech) used the phrase “double language” to explain how the 1995 Family Proclamation tried to balance the patriarchal order of marriage with contemporary views on gender roles. That’s why you get descriptions of mothers and fathers as “equal partners,” alongside fathers who “are to preside” while mothers primarily “nurture.”

I see that same strategy in what’s known as the Utah Compromise, where anti-LGBTQ discrimination legislation was passed in housing and employment, so long as that housing and employment was not provided by the LDS Church or other religious institutions. In other words, the compromise was that religious exemptions to allow discrimination were written explicitly into the law. That seems like a big deal to me, especially for institutions that receive federal funds. “Just knowing the government is funding discrimination can be harmful,” says Joe Baxter, a former Mormon and legal fellow at the Religious Exemption Accountability Project.

Double language denies harms

Dallin H. Oaks was President of BYU from 1971-1980. Max Ford McBride’s thesis on studying the using electroshock aversion therapy to change the sexual orientation on 14 gay men was published in 1976., Accounts of students receiving or being referred to aversion therapy on campus also date from that period. When asked about it, Oaks said that electric shock treatments “never went on under my administration.”.

Then he said, “Put that to one side.” It may seem a throwaway remark, but it exemplifies the biggest barrier to progress: an unwillingness to take accountability and admit harms.

In his public talk, Oaks describes advocates for nondiscrimination and advocates of religious liberty as “two groups” that “have been drawn into conflict” and asks them to cooperate and seek “fairness for all.” Later, he says, “Conflicts between religious liberty and nondiscrimination principles are exacerbated when advocates for nondiscrimination paint people of faith as bigots, and when people of faith fail to appreciate the brutal history of the basic human rights of marginalized groups, such as gays and lesbians.”

It is progress that this Mormon leader is using words like “gays and lesbians” and not (as he did in the 1970s) advocating criminal penalties for homosexuality. But not only is he failing to appreciate his own role in the ‘brutal history,’ he wants it “put to one side,” perhaps the underside of a rug.

Hannah Comeau, a queer UVA law student and former Mormon, thought the rhetoric was a tactic to tell the public not to look into harms and discrimination the Church caused, and that his refusal to even acknowledge it undermines his credibility.

Baxter added that the description of ‘two groups drawn into conflict’ denies the power imbalances and vulnerability of queer students. Podcast organizer Gerardo described his constant fear as a BYU-Idaho student in a relationship with his current husband, where revelation of his relationship could have denied him his degree and US residency. Even after graduation, he worried the university would find a way to hurt him. Chloe Fife, a transwoman, UVA law student, and former Mormon, recalls a speech Oaks gave telling families to distance themselves from queer members. As a devout teenager she knew that she couldn’t talk about who she was to the people she loved for fear of impeding their eternal opportunities. ‘I don’t know how he expects me to approach him if he’s not willing to have a discussion about how his words have harmed people,’ she says.

Connell O’Donovan, a historian whose work garnered a lifetime achievement award from the Utah Pride Center, calls the hypnotherapy he endured to try to change his orientation as the single most devastating experience of his life, and sees Oaks’s response to the question as a tragic loss. ‘It could have been a super-healing moment that brought growth and progress.’

Surely a man as brainy as Oaks also would have recognized the opportunity. So why didn’t he take it?

image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dallin_H._Oaks2.JPG

Related reading

President Oaks: There is a need for ‘both religious protection and fundamental fairness’ (Deseret News)

Why was last week’s speech on LGBTQ rights ‘the most difficult’ of LDS apostle Dallin Oaks’ career? (Jana Reiss, Religion News Service)

Dallin Oaks says shock therapy of gays didn’t happen at BYU while he was president. Records show otherwise. (Salt Lake Tribune Sub req’d; I haven’t read, but it’s been praised)

School of Law event with Dallin Oaks draws protest from Lambda Law Alliance (Cavalier Daily; in the podcast, Comeau said she wanted Oaks to be able to speak but objected to how he was being portrayed as an LGBTQ ally)

Great article. O’Donovan is right. It could have been an opportunity for healing. I’m afraid Oaks is carrying on the proud Mormon tradition of gaslighting. I was reminded of an Ensign article about racism that had me steaming some 20 years ago. Thanks to the Google gods it popped up in a single search: “How grateful I am that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has from its beginnings stood strongly against racism in any of its malignant manifestations.”–Elder Alexander B. Morrison of the Seventy

https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/ensign/2000/09/no-more-strangers?lang=eng

Re: “Then he said, “Put that to one side.” It may seem a throwaway remark, but it exemplifies the biggest barrier to progress: an unwillingness to take accountability and admit harms.”

This hits the nail on the head, but the frustrating thing is that it’s hard to come up a solution or any way of dealing with this. The church’s whole selling point is that they have a direct line to God. Any admission of error challenges the church’s whole foundation.

Regardless of the issue at hand, whenever some harm really comes from the top levels of the church itself, they can’t admit to errors and make amends. They can only gaslight by either (1) blaming everyone else, or (2) pretending like it never happened and painting anyone who would bring it up as mean haters who are hating on innocent church members out of the meanness of their black hearts.

I’m getting to this point where I’m bewildered by anyone who would imagine that the church would ever take responsibility for anything bad — as opposed to just overclaiming responsibility for any good done by its members and then using them as a human shield to protect the church from criticism…

OTOH, since the harm and gaslighting continues to hurt people who have a connection to the church, I don’t think that critics should just throw in the towel and give up.