In the 1980s, three Mormon men “exercised unrighteous dominion” over me, which is a Mormon way of saying that they abused their authority to gratify their own egos and hurt someone else. Each of them did the same thing: they demanded that I sit in a room alone with them and submit to snoopy questions and conversation set according to their agenda without concern for my preferences or comfort—even though they had no official authority over me and had no jurisdiction to request such a thing.

Grooming is crucial. The first time I had an interview with a Mormon man was shortly before I turned eight: my dad took me to talk to the bishop, who determined whether or not I was worthy to be baptized. That was the only interview where one of my parents was present. Beginning with my twelfth birthday, I regularly underwent interviews with priesthood leaders. I will be honest: some of those were helpful and comforting. When I was a profoundly unhappy 13-year-old, it helped me to have my religious questions and my personal anxieties taken seriously and addressed with compassion by an adult.

But a lot of the conversations sucked. And the general expectation that I would just sit in a room with a guy from church even if he was being a jerk made it normal that I would do that even when it occurred outside of normal procedures.

The first man who did this was the father of one of my college friends, or more accurately a friend who was also a distant cousin. This guy was a relative by marriage. He heard that I’d done something he didn’t approve of, so when I was visiting my cousin, he called me into the living room for a private interview. Everyone left and I was stuck with this guy, who told me what he thought of my behavior and called me to repentance. I was pissed, but I really didn’t have any way out of it, so I made nice so I could get out of there and not be uncomfortable for the rest of the visit. This person is now dead.

The second man who did this was a teacher at the MTC who, I learned later, hated women and chose one woman in every class he taught to belittle, torment, and tame. Even though he was not my “stewardship teacher” and had no authority to interview me, he took me into a shitty classroom in the MTC, grilled me on my belief, behavior, and worthiness. He would not let me out of that room, and got more and more personal in his insults and condemnations of me, until after about an hour, I finally just burst into tears.

Well. That was a revelation, because I knew the minute it happened that it was what he’d been hoping for, and that it actually turned him on.

It was 1985 and if the term “rape culture” existed I hadn’t heard it, but I still tried to talk about rape and sexual violence when I complained to the guy’s supervisor, because I had a sense that he had purposely inflicted spiritual violence on me because he enjoyed it. I googled him a couple of months ago; he lives within a few miles of me.

The third guy was Robert J. Norman, who was the director of the University of Arizona’s Institute of Religion, where I was “most valuable senior” or some such thing before my mission. He came to my mission farewell and even insisted on participating in setting me apart after my farewell, which I was ambivalent about but couldn’t find a nice way to object to.

One day very shortly after I got home from my mission, I was sitting in the Institute lobby minding my own business. Bob walked up to me and said, “Holly, come talk to me in my office.”

“I’m waiting for a friend,” I said. “We’re going to lunch as soon as he finishes class.”

“He can wait for you,” Bob said. So I went into his office, where he proceeded to interrogate, lecture, and rebuke me for an hour. Among other things, he said that he never imagined I would be able to finish a mission, because I had too many questions and couldn’t be as docile he deemed appropriate. He said that people who imagine that they know better than the general authorities invariably come to a bad end. (More on that later.) He became even more personally insulting, and when I finally lost my temper and then burst into tears in large part because that’s what he was trying to get me to do, he said, oh so derisively, “Look at you, blubbering and hysterical! And you call yourself a woman?”

It was at that point that he had to leave to go teach a class. I firmly believe that that is the only reason he gave me permission to leave his office. I was still crying when I left.

It’s true that theoretically, I could have just gotten up and walked out of his office when I was under attack and struggling to make my world cohere. Theoretically, I could have violated twenty-three years of religious indoctrination and just left. Practically, however, that was essentially impossible for me.

Bob’s predecessor never would have done such a thing, both because he was a nicer, more compassionate person, and because he didn’t make it his job to police people’s behaviors and speak to for God in telling them what was wrong with them. Which is probably why he was needed to run the Institute at Harvard, where people might expect more intellectual freedom than Bob would allow.

Unsurprisingly, I avoided Bob assiduously after that, and I also didn’t bother to disguise the utter contempt and loathing I felt for him. One Sunday I was standing in the hall talking to my friends while we waited for sacrament meeting to start. He walked up and shook hands with all the guys, then stuck his hand out to me. I just looked at it. So he said, “Shake hands with me, Holly.”

I rolled my eyes and sighed loudly. “Sure thing, Bob,” I said, taking his hand. Everyone else tittered nervously, and Bob was visibly shocked that I called him by his first name instead of Brother Norman, but I have pretty much always referred to him as Bob since then.

In other words, Bob was bossy, nasty, and mean, with a high very opinion of his own authority and righteousness and little sense of the limits of either. In the 1990s, he was called to be a mission president. He was called to be a mission president because he was bossy, nasty, and mean, with a high very opinion of his own authority and righteousness and little sense of the limits of either. He was the sort of person the church wanted to elevate and reward so that he could more easily condemn others.

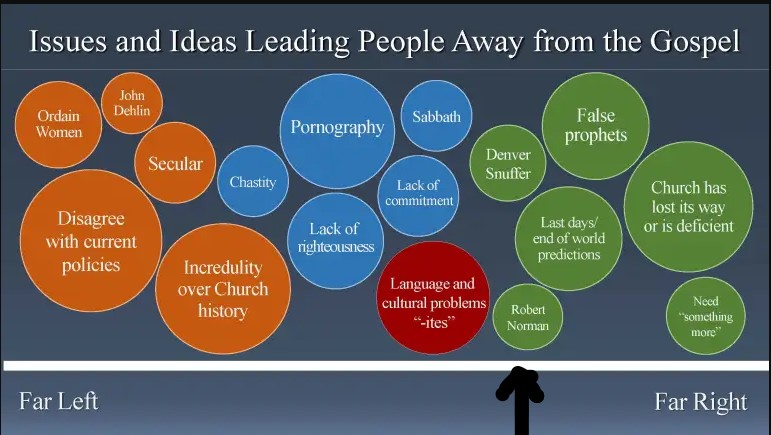

Recently, on a whim, I googled this guy. It took me a while to determine that the asshole I knew as Bob Norman is now the asshole known as Robert J. Norman. If reports are to be believed, he has resigned from the church for a variety of reasons including a purported sense that he knows better than the general authorities, which means that the bad end he envisioned for others in the twentieth century is the bad end he has come to in the twenty-first. He is reportedly so full of his own righteousness that the church hierarchy considers him a threat!

But the church never punished him for exercising unrighteous dominion. Instead, the church rewarded the attributes and behavior most likely to cause unrighteous dominion. And now they’re surprised that this complete tool they empowered and enabled could be a tool of their own undoing?

I posted about this on my Facebook page earlier this week. A friend mentioned that as a missionary in Arizona in the late 1980s, he had known Bob (in part because Bob may have been in the leadership of the mission–his memory was a bit fuzzy). This person said that even then, Bob aroused a lot of hero-worship, which he called “weird and cultish.” He also told a story about Bob micro-managing what sort of music a new convert could have performed at her baptism.

The church promoted Bob because he loved policing Mormonism and was devoted to indoctrinating people into it, and because he had (what passes in Mormon circles for) charisma, all of which make him the sort of person who can attract followers, particularly as the more elderly members of the upper echelons of the gerontocracy see their charisma wane and remain fixated on their fear and loathing of queer people. The church is like Dr. Frankenstein, creating all these monsters, and then watching in horror as the monsters attack their maker.

All of which is to say that this is a great example of the church being hoisted with its own petard, which I never tire of pointing out means that someone is blown up with their own fart.

Thanks for this post! Speaking out is so important, even if years later. The intersection of smug righteousness and toxic masculinity is noxious indeed.

Interesting that the Church creates it’s own monsters.

I haven’t thought about it too hard, but it seems to me that it’s not unusual for organizations to create their own threats. In March 2003 (I remember because it was during the run-up to our invasion of Iraq, and the section on Vietnam made crystal clear why the Iraq war would be a massive mistake and an utter debacle), I read The March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam, Barbara Tuchman’s analysis of “the pursuit by government of policies contrary to their own interests, despite the availability of feasible alternatives.” One case study is the way the Renaissance popes made something like Martin Luther’s protest of them inevitable by being rapacious, greedy bastards whose behavior was intolerable to any decent person.

For that matter, Joseph Smith created major threats to himself by codifying justification for him to sleep with anyone he wanted to. Who knows how long he would have lived if he had been able to keep his lust in check.

Tuchman’s book certainly continues to be timely, doesn’t it? And, yes, Joseph did create his own threats. He certainly lacked the survival skills of subsequent church leaders. It’s an amusing dichotomy these days–the LDS Church eggs on these big-headed patriarchs so long as they stay within the ranks. But when they draw outside attention the Brethren fall all over themselves to condemn the narcissists’ behavior, for the sake of preserving the church’s “mainstream” image.