Guest post by MJBY (The author teaches creative writing at Brigham Young University and has written extensively about blacks in the American West).

Marshall, Missouri Ive known the name of the town for a decade now, since I teamed with Darius Gray to write three books and produce two documentaries on blacks in the Old West black Mormons, to be specific a subject which causes most to raise a skeptical brow. The usual response is, You mean there were some? Or I thought you all didnt let Blacks join your church until what 1980? Or this one, which we heard at a Los Angeles book fair: Didnt you Mormons consider blacks one slim notch above monkeys until, like, last year?

As a white Mormon woman, I wince at such questions. I am fully aware of the appalling statements some of our Church leaders made about blacks throughout Mormon history. You see some classes of the human family that are black, uncouth, uncomely, disagreeable and low in their habits, wild, and seemingly deprived of nearly all the blessings of the intelligence… said Brigham Young in 1859 (Young 291) one example of many I could cite. And I am all too familiar with our reputation for being a racist church. Even Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid has been publicly accused of racism simply because hes a Mormon. Columnist Mychal Massie asserted in 2004: Reid’s comments [about Clarence Thomas] should surprise no one repulse, sicken and anger, yes, but surprise, no. He is simply being true to his inbred familial heritage. Mormons believed, as Reid’s comments indicate he still does: “Cain slew his brother … and the Lord put a mark upon him, which is the flat nose and black skin”(Massie).

For Darius, who is a black Latter-day Saint, presumptive questions about Mormonism and race sting deep and often come with the bite of accusation. Usually, the questions are phrased in more direct ways to Darius than they are to me: How can any self-respecting black man be a member of a church which… This is followed by any number of reprehensible quotes from dead Mormons supporting the LDS priesthood restriction, a restriction which not only disallowed black men to be ordained to the priesthood (all other Mormon men are generally ordained at age twelve), but forbade all people of African descent from entering Mormon temples to participate in the profoundly significant endowment ceremony. The policy was in place from 1852-1978.

Darius learned about the priesthood restriction the night before his scheduled baptism and wrestled with the information for hours. He determined not to be baptized, and then wrestled some more. Finally, he prayed, and then prayed again. I have heard him tell the story no fewer than twenty times. It never changes, regardless of his audience. Darius Gray believes he had a revelation from God telling him to join the LDS Church even with that restriction in place. He was baptized.

The next year, 1965, he moved to my hometown, Provo, Utah to attend Brigham Young University. At the time, Provo was the largest city in the United States without a resident black family. It was a year when anti-Communist groups were forming like overlapping viruses. W. Cleon Skousen created the Freemen Institute just off BYUs campus a center for ultra conservative conversation and speculation. Even at Provo High School, my history teacher had Brother Skousen come and talk to us about The Naked Capitalist (Skousens sparsely documented, fear-mongering book) and the nefarious Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), which, said Skousen, was actually controlling everything in the world. Suspicion hovered in the air; Skousens conspiracy theories came as unauthorized supplements to my religion, and even my young classmates imagined the most innocuous events as Communist plots (Communism also being controlled by the CFR).

At BYU, Darius was invited to see a film about Civil Rights in the universitys only theater. As it turned out, the film was called Civil RIOTS and accused Martin Luther King Jr. of being complicit with Communists. After being called into the Deans office and told that complaints had been levied against him for associating with white girls, Darius left my hometown on a dead run. He returned to Utah one year later, when the LDS-owned television station, KSL, hired him to be a reporter. He was a trusted Negro, and when conspiracy theories spread to include all Civil Rights workers (in league with Communists, of course, and angry at Mormons because of the priesthood policy), and an alleged prophecy by Church president John Taylor started making the rounds in Mormon homes, the rumors were rampant and horrifying. The U.S. Constitution was going to hang by a thread, and blood would run down the streets. Where would the blood come from? I remember well when my familys home teacher (fellow congregant) read us the prophecy suggesting that Negroes would invade our temples, ravish our women, and shed our blood. I have never been able to find the document I heard as a young teen, but I have found records of others who remember hearing it also.

Darius got a much more personal introduction to the terror which permeated Utah during the latter years of the 1960s: The police chief, Dewey Fillis, a friend of his, showed him the actual battle plans for dealing with the predicted Negro invasion how the National Guard would be mobilized, where the troops would be bivouacked and stationed, where blockades would be set up, etc.

We all lived in fear. I lived on the white side of it. Darius, on the black side, actually made arrangements to get his wife out of the state, should things get violent. He also had plans for getting himself out by horseback, if public transportation became too dangerous for a black man. And he got permission to carry a gun.

Finally, all LDS bishops were instructed by the Mormon leadership to read a statement over the pulpit debunking the Taylor prophecy. We retreated from full alert to half-alert, though Darius continued to fear for his own safety and his wifes, and had to defend his right to be on Temple Square several times.

I did not meet Darius Gray until 1998. Then, one by one, I met his whole family, living and dead. I met them because they were included in the books Darius and I wrote.

Dariuss grandfather, James Louis Gray, was born a slave in Marshall, Missouri in 1859. James was born to Louis and Gracie Gray, slaves of Mortimer and Emily Gaines. Jamess wife, Annie, gave birth to fifteen children, two of whom could have passed for white. One of them did pass. The other, Dariuss father and namesake, chose to live as a black man, and carried two copies of the Negro National Anthem – Lift Every Voice – in his wallet.

I know not only the name of Marshall but of nearby towns Boonville and Sedalia because of my research. I had imagined these towns in the beginnings of the Civil War, where they provided rehearsal stages for the massive battles which would ensue at Antietam, Gettysburg and elsewhere. Confederate general Sterling Price made a passionate speech in Marshall on November 16, 1861, urging its men to join the gray side of the war. Are we a generation of driveling, sniveling, degraded slaves? he shouted from Marshalls city center. Or are we men who dare assert and maintain the rights which cannot be surrendered? In the name of God and the attributes of manhood, let me appeal to you by considerations infinitely higher than money! (Price 287). As we wrote our books, we knew that Mortimer Gaines had likely been in Prices audience. Perhaps his slaves Dariuss great grandparents had been nearby as well.

Sterling Price was the very man who had once stood guard over the founder of the Latter-day Saint religion, Joseph Smith, when he and others were imprisoned in Richmond, Missouri. Price had also led the Chariton militia protecting the Mormons from further violence after they were expelled from Missouri in 1838, and their hopes of building a temple in nearby Independence were dismantled along with their community. My own ancestors, Chandler and Eunice Holbrook, were among those who endured what we Mormons refer to as the extermination order in which Governor Lilburn Boggs ordered that the Latter-day Saints be driven from the state or exterminated. Though there had been some threats from Mormons (Church apostle Sidney Rigdon had used the phrase war of extermination in a July 4th, 1838 oration which challenged any who came against the Latter-day Saints), the suffering of the Mormons was undeniable. My own ancestors were literally driven from their homes. Chandlers brother, Joseph Holbrook, recorded the events starkly: My wife had very poor health during the fall and winter[1838] by … having to remove from place to place as our house had been burned and we were yet left to seek a home wherever our friends could accommodate us … [We] were now destitute (Holbrook).

Mormons have a sad history in Missouri. As do blacks. Only two years before General Price issued his ardent invitation, two black men had been lynched and one burned at the stake over alleged crimes in Marshall. The Stauntan Spectator described the burning in lurid detail:

A correspondent of the St. Louis Democrat, writing from Marshall, Saline county, Missouri, on the 26th ult., says: Some time ago, you will recollect, a negro murdered a gentleman named Hinton, near Waverly, in this county. He was caught after a long search, and put to jail. Yesterday he was tried at this place and convicted of the crime, and sentenced to be hung. While the Sheriff was conveying him to prison he was set upon by the crowd and taken from that officer. The mob then proceeded to the jail and took from thence two other negroes. One of them had attempted the life of a citizen of this place, and the other had just committed an outrage upon a white girl. After the mob got the negroes together, they proceeded to the outskirts of the town, and selecting a proper place, chained the negro who killed Hinton, to a stake, got a quantity of dry wood, piled it around him, and set it on fire! Then commenced a scene which for sickening horrors has never been witnessed before in this, or perhaps any other place.

The negro was stripped to his waist, and barefooted. He looked the picture of despair – but there was no sympathy felt for him at the moment. Presently the fire began to surge up in flames around him, and its effects were soon made visible in the futile attempts of the poor wretch to move his feet. As the flames gathered around his limbs and body, he commenced the most frantic shrieks and appeals for mercy – for death – for water! He seized his chains – they were hot, and burnt the flesh off his hands. He would drop them and catch at them again and again. Then he would repeat his cries; but all to no purpose. In a few moments he was a charred mass – bones and flesh alike burnt into a powder. Many, very many of the spectators, who did not realize the full horrors of the scene until it was too late to change it, retired disgusted and sick at the sight.

May Marshall never witness such another spectacle. (Spectator, 1859)*

In September, 2009, Darius and I showed our documentary, Nobody Knows: The Untold Story of Black Mormons, at the John Whitmer Historical Association in Independence, Missouri. There, I got to see the very property where my ancestors had envisioned a temple, the very land they had been driven from. As we continued our journey, I saw road signs pointing towards Sedalia and Boonville, and towards Marshall.

Then there we were, in Dariuss ancestral home. We went to the public library, where a genealogist and historian worked. He and Darius talked a bit about all of the names in the Gray/Gaines ancestry, and we prepared to go to the cemetery. It was on our way out of the library that I saw the magazines on display. Patrick Swayze, who had died that week, took up several covers. Glenn Beck stuck his tongue out under the title TIME. And that was when I had what I shall simply call a moment.

I was caught in history, gazing at library patrons working on computers which linked them to current events all over the world, and I was simultaneously aware of horrific events which had happened right there in that little Missouri town events which were rooted in my co-authors life story. And Glenn Beck was sticking his tongue out at me like a petulant four-year-old.

Why did Becks infantile sneer matter? Because Beck is a Mormon. Because his mocking presence in the small town of Marshall, Missouri meant he was sticking his tongue out at patrons in every library in the nation. Because the city of Provo, Utah where I still live and now teach sometimes invites him to be part of our Freedom Festival and host our Stadium of Fire, as though his ultra right, self-assured conviction and his simplistic view of contemporary issues comprise a worthy rsum. Because he is a disciple of W. Cleon Skousen, whose conspiracy theories resulted in students spying on each other and on their professors at BYU and fomented terror and suspicion throughout Provo even at Provo High and created a climate which made Darius fear for his familys life. Because Beck has said such race-baiting things as, This president has exposed himself as a guy … who has a deep-seated hatred for white people, or the white culture (July 28). (What on earth does he mean by white culture? Is it in the tradition of the Coen Brothers white supremacists in O brother Where Art Thou?: We have gathered here to preserve our hallowed culture and heritage…) Because on Fox News he loops a tape of Reverend Jeremiah Wright saying Not God bless America…, as though it were something new and newsworthy, and as though Wright had never said anything else. And because people think he represents me and even Darius, inasmuch as we all call ourselves Latter-day Saints.

I said something sotto voce and unprintable to the image of Becks tongue, and we headed to the cemetery.

I had never seen a segregated cemetery before. I was touched, disturbed, intrigued, energized.

A bluff overlooks the grounds, housing fifteen mobile homes, all rusty at the seams and sitting like appetizers for a tornado. A gravel path divides the white part of the cemetery from the colored. The white section is immaculate, kept up by the municipality, Darius informed me. Not so the black side. I set out to find the name GRAY on that side, where headstones were knocked over, moss-covered, and often simply absent. Many graves were nothing but coffin-size indentations in the earth. I imagined they once had been marked by rudimentary crosses, long since decayed. One grave had the name carved into it as though with a pen knife, the etchings deep but uneven. A fallen tree, as dead as anything else there, sprawled over eight yards of graves. One headstone was hidden within a small grove of saplings. Darius read the names on the tombstones and wondered out loud if the person buried in this or that plot had known his family. He was certain most had.

I looked at the birth and death years. What had these people seen? What had their lives been? 1896-1960. Born in the year of Plessy v. Ferguson; died on the dawn of the most intense years of the Civil Rights Movement. 1856-1908 this person lived through the Civil War. One grave memorialized the deceased (born in 1857) as faithful servant … for seventy-seven years. Some were born the same year I was 1955 the year fourteen-year-old Emmett Till was murdered in Mississippi for whistling at a white woman, and the year Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man. They would have lived through the same years I have, but on the colored side, enduring Jim Crow laws for another decade, and Jim Crow attitudes for years beyond any laws passage.

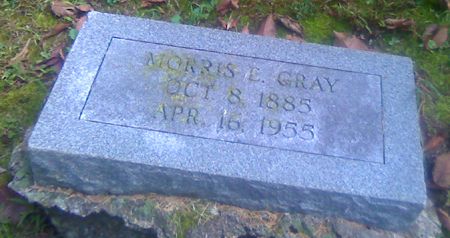

Finally, I found the name Gray. I shouted to Darius, who was nearly out of earshot. Do you know the name Morris? Morris Gray?

Morris Elijah Gray, Darius said as he joined me. He had gone to the funeral in his childhood. The stone was partially uprooted, but the name still clear. Hello Uncle Elijah, Darius said. We knew others of his family were buried nearby, but their headstones were gone.

After some long, meditative moments, we headed back towards Independence in many ways my ancestral home. Glenn Becks nyah nyah expression still haunted me. I could imagine him echoing Sterling Price: Are we a generation of driveling, sniveling, degraded slaves? determined that his way was the only way. In the name of God and the attributes of manhood, let me appeal to you!

I can forgive Sterling Price, a slaveholder who grew up with traditions we find appalling now. I can deal with the misbegotten statements of my past church leaders. I have the same attitude towards them as Union General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain expressed in reflecting on the dignity he granted his surrendering enemies: Although, as we believed, fatally wrong … blind to the signs of the times in the march of man, they fought as they were taught, true to such ideals as they saw, and put into their cause their best (Chamberlain 158). Past leaders of my faith also fought as they were taught and passed on ideas and traditions inherited from generations before them. Part of my faith is to believe that with Gods help, we may and must become better.

Perhaps that is why Glenn Becks mocking, dismissive, sneering tongue and absurdly furrowed brow provoke me to unspoken epithets I would not normally even think. He is inviting me and any who will listen to the world I was terrified of as a child, and which, by the time I was in high school, I realized was an outlandishly hokey creation a world which invents and obsesses on cloaked conspiracies; a world which encourages racial division; a world which loops a soundbite (Not God bless America…) and calls it an identity. A world which reduces the President to a well-spoken, credit-to-his-race guy who hates white people. Beck exhumes skeletons from our closets and coffins, and unholy passions from our past which should stay buried or be instantly cremated if they still happen to yet be hovering. For me as a Mormon, Glenn Becks invitation to return to childish things forces me to confront anew the unsavory aspects of my religions past, and all the things we Latter-day Saints are now attempting to heal.

Independence, Missouri. An aptly named city, where my ancestors tried and failed to build a community, and then were driven out by gangs terrified that conspiratorial Mormons would take over everything.

God make us independent and free us from stupid ideas. Emancipate us from a worldview which foments fear from invented semiotics and imagined plots. Such fear is a form of terrorism (emphasis on terror), and the trigger of unthinkable violence and mindless mobocracy. Let us not be hostages of any false saying our religious or political leaders ever offered. We have suffered enough, and we have caused enough suffering in others.

We Mormons believe in eternal progression. Lets get on with it.

Chamberlain, Joshua Lawrence. Bayonet! Forward. Gettysburg: Stan Clark Military Books, 1994.

Holbrook, J. (n.d.). Early Saints.

Price, S. (1909). Speech. In J. McElroy, The Struggle for Missouri. Washington DC: National Tribune Company, 1909.

Staunton Spectator. (1859, August). Negroes Hung – One Burnt at the Stake.

Young, Brigham. Journal of Discourses, Volume 7.

*In no way should the fact that Mormons were persecuted in Missouri or elsewhere be equated with what blacks suffered during the four-hundred year holocaust of slavery and in the subsequent years of seeking full emancipation and equality. To suggest that there is a direct parallel would trivialize the entire Civil Rights Movement and the horrors which blacks and others – endured in the quest for freedom.

Fascinating article — thanks for sharing!

Thanks for posting this!

Thanks for this very interesting article,and I have enjoyed reading it very much. I certainly do admires Margaret Young for her great her writings. I appreciate her sharing her thoughts, and they were stated in a loving spirit.

Chester Lee Hawkns

I see a lot of interesting articles on your website. You have to spend a lot of time writing, i know how to

save you a lot of time, there is a tool that

creates unique, google friendly articles in couple of minutes, just search

in google – laranita’s free content source