In his memoir, the former President of Affirmation shows how to embrace both queerness and faith

The LDS Church’s stance against gay people has evolved in the past half century. Homosexuality is no longer blamed on sexual abuse, poor parenting or, as Spencer W. Kimball said, an embarrassing “search for excitement.” The Church no longer prescribes mixed-orientation marriages or electroshock therapy to “correct” orientation. Apostles have stopped arguing that no one can be born irrevocably gay. (“Why would our Heavenly Father do that to anyone?” Boyd K. Packer asked at a 2010 General Conference.)

In 2015, after the US Supreme Court allowed same sex couple to legally marry, the Church proclaimed any Mormons who did so apostates, only to reverse itself in 2019. It now urges celibacy while still maintaining that mixed-orientation marriage is required for full exaltation. Trans people can’t hold leadership roles or attend the Relief Society or Priesthood meeting of choice, but at least the Church acknowledges the existence of “people who identify as transgender” and invites them to sacrament meeting.

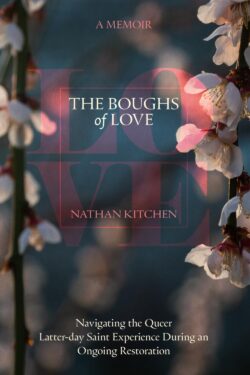

Nathan Kitchen has lived through many these upheavals as an individual and leader within Affirmation. Unfortunately, Kitchen says, the Church’s updates focus on achieving societal acceptability and preserving heteronormative status: reaching a complicated, sincere acceptance is not a priority. Fortunately, this is what he exemplifies in his memoir, the Brodie-nominated Boughs of Love.

Kitchen covers much ground in his hefty 450 page book: he recounts silencing himself into the “safety of obedience” as a young man, coming out to his wife many years and children later, maintaining ties with his children, shepherding Affirmation’s support for gay fathers, taking on broader leadership roles through the Church’s exclusion policy and the global pandemic, and choosing a fulfilling marriage over formal church membership.

One of Kitchen’s recurring themes is how Church leadership creates false, toxic binaries. It adopts an “us versus them” mindset that keeps the gay community on one hand and the LDS on the other. That, Kitchen says, leaves out what’s between, the heart. It also puts LGBTQ people on “a symbolic cross.”

Those poor souls caught at the intersection are treated as pawns in a public relations game rather than people to be valued and supported. As a leader within Affirmation (including president from 2019 to 2022), Kitchen describes meeting with Church representatives to discuss queer members’ spiritual needs, such as suicide prevention, and the Church insisting that “religious freedom specialists” attend. “What do you do as a human being,” Kitchen asks, “when you are reduced to someone’s sincerely held religious beliefs?”

Sexual minorities are pressured not to voice the pain and isolation that they feel within the Church. If they do, they risk being scolded as lacking faith or labeled as bitter. Instead, Kitchen says, there needs to be an embrace of “the beautiful messiness of queerness.” A key tool for this is sharing unvarnished stories of the queer Mormon experience. Kitchen also grounds his case in scripture, pointing out that Doctrine and Covenants 123 calls on Saints to publish an account of their sufferings and persecutions.

Kitchen also deploys careful choice of words. “Faithful” is a term that church leaders employ in judgement, he says, so he describes himself instead as a person of “faith.” This helps him retain his sense of self after his local church leaders summarily dismiss Kitchen’s religious sincerity when he decides to marry the man that he loves, Matthew Rivera.

The complicated, time-tested, tender and specific relationships that Kitchen’s children, siblings, and parents forge with Rivera stand in stark contrast to the clergy who are so ready to dismiss both Kitchen’s relationship and his own divine confirmation of what is right for him. Kitchen’s decision to resign rather than be excommunicated is poignant and powerful.

I cheered out loud when Kitchen, on a tour of the Mesa Temple with other LGBTQ leaders before its rededication, introduces Rivera to a General Authority. This is apparently the first time any senior brethren had encountered a man introducing his husband in such a venue. That sense of victory was quickly crushed when an apostle brings the tour to a sealing room, emphasizing that sexual minorities have no place in the Mormon plan of salvation. “It was the capstone moment of exclusion,” Kitchen writes.

That moment underscores why Kitchen undertook his work at Affirmation to share stories and build community. His haiku in the book sums it up perfectly.

Our Family Proclamation

At the Tree of Life

Standing Under Boughs of Love

No one left behind

Read this post on substack and subscribe!

This was a painful review to read. For many years, I held the same hope, that the LDS church would eventually see the light. Now that I know it will never happen (and at this point wouldn’t change my view of them in any event), it’s painful to see others going through that same process of realization.

I imagine anyone who has tried to change the church from within will identify with Kitchen’s story. I especially like his distinction between “faithful” and “person of faith.”

Thanks for the review. Sounds like a worthwhile read!

The haiku at the end is lovely. Sounds like a great book!

This powerful account deeply resonated with me. Kitchens vulnerability and courage in navigating his faith, love, and the churchs rigid binaries are truly inspiring. His story highlights the human cost of institutional exclusion.