Some of my closest family members treat me badly because their church tells them to. I long tried to excuse them because I remembered when I was deceived by the LDS church as well.

Then I remembered I Corinthians 10:13, “There hath no temptation taken you but such as is common to man: but God is faithful, who will not suffer you to be tempted above that ye are able,” and I realized that at some point, we’re all responsible for our own abusive behavior, no matter what cultural mindset we’ve been immersed in.

When I assigned my students Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” many were shocked and outraged to imagine a society that could act as cruelly as the one depicted in the story. Then I asked if they could imagine a future historian looking back on our time and saying the same thing. “What do we do routinely in our culture someone else might consider unacceptable in the future?”

After some heated discussion, students suggested head injuries in football, boxing matches, and horse racing. Others then suggested boiling lobsters alive or big game trophy hunting. Next came a lack of universal healthcare, long prison sentences for non-violent drug offenses, and forcing students to take on decades of student loan debt.

Subsidizing fossil fuel corporations and the destruction of our climate.

The students began thinking, which is all a teacher can really hope for.

But if my students could begin reassessing acceptable morality after one short story and a single class discussion, we’re all in a position to do at least a minimal amount of self-reflection.

As a Mormon missionary in Rome, I was assigned to guide “greenies,” new missionaries who’d just arrived from the U.S. When one of them wasn’t performing at a level my zone leaders deemed acceptable, I was ordered to hound the man until he got in line.

In this closed, cult-like culture, peer pressure and conformity were powerful forces, but I simply couldn’t follow the directives of my leaders. I instinctively knew it was wrong to treat my missionary companion badly. If he was sinning, that was his prerogative. After all, in the Pre-Existence when Lucifer offered to force everyone to be good, Heavenly Father rejected that plan.

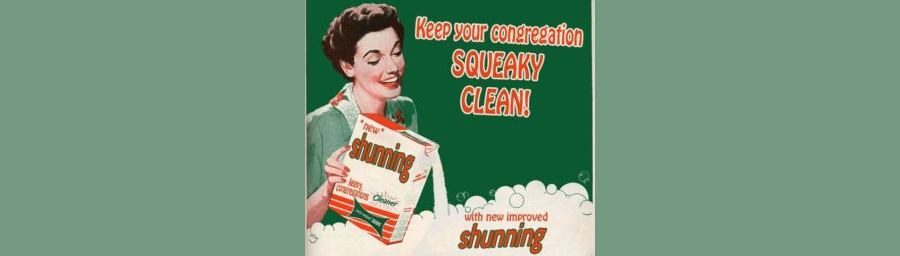

So when modern LDS leaders—apostles and prophets—urge members of their church to disinherit their children who don’t attend services faithfully, when they urge members not to accept their children’s same-sex partners, when they urge members to behave in other cruel ways, those church leaders are responsible for leading their followers to sin. But those followers are responsible for agreeing to commit those sins.

“There is beauty all around when there’s ‘tough love’ at home.”

Doesn’t quite have the same ring as the popular hymn. And justifiably so.

Mormons discount Brigham Young’s acceptance of slavery because “he was a man of his times.” But even in the time of Brigham Young, there were abolitionists who could look past societal norms. He was responsible for choosing not to do so.

Cruelty is cruel, no matter who tells us otherwise. Shrugging off our personal responsibility when we hurt family members—or complete strangers—cannot be the guiding principle in the lives of people who hope to become gods.

Of course, it’s easy for me to see the flaws of my family members who treat me badly. That’s hardly a stretch. Their behavior is blatantly obvious.

What’s harder is to examine the ways I’m also conflating love with cruelty, or complacency with cruelty, or ignorance with cruelty.

We can’t turn into paragons of 100% virtue overnight, but we can tackle one blind spot at a time and become a tiny bit better as human beings rather than excusing every cruelty just because others do. We can choose to be conscious of and responsible for our personal behavior.

Our devout family members may be tempted by LDS leaders and LDS culture to behave cruelly, they may be directly led to cruelty, but they’ll never tempted or led beyond what they can resist. That’s according to their own doctrine, so we can hold them to it.

And we can stop giving them a pass just because they give themselves one.

Great insights! I feel like this post has so many great discussion topics embedded in it (e.g. can you think of any other things that are normal today that might be seen as shockingly cruel by future generations?)

On a personal level, this ties in with my most recent post. I have a relationship that has deteriorated because the other person did something cruel — and we can resolve the issue because they refuse to talk about it. They won’t even admit they’re refusing to talk about it (which might open a discussion as to why), but instead use an endless stream of rhetorical games to evade the question and shut down the discussion before it can happen.

It reminded me of the “Young Women’s Values” song that I was taught in LDS church as a teenager: “I understand the meaning of ‘accountability’ — every choice for good or ill is my responsibility.”

I’m not sure how this works, but somehow it seems like they think that if you’re teaching someone a lesson through tough love, you don’t have to justify it, explain it, or even acknowledge that you did it…

Thanks for this, Johnny. Kindness really isn’t that difficult!

Yes! And I think what unites these questions is the need for thinking and curiosity. If people let themselves be curios about someone’s life, they hold off on the condemnation and, often, the cruelty. And both of these enforce conformity, so of course cultures that depend on conformity cast curiosity (aka questioning aka ‘doubting’) as a threat. Thanks Johnny!